Rhapsody of Youth (Wakakihi no Kyoushikyoku)

by Yamada Kōsaku, the Handwritten Manuscript

About the Document

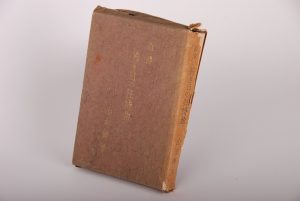

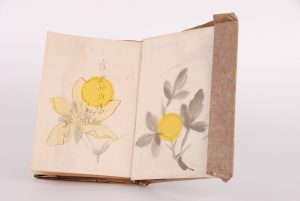

The document is the last version of Yamada Kōsaku’s (9 June 1886 (Meiji 19) – 29 December 1965 (Shōwa 40)) autobiography, Rhapsody of Youth (the first edition was published by Dainihonyūbenkaikōdansha in 1951 (Shōwa 26). Writing in his 60s, Yamada, now well known as the composer of the songs Akatonbo, Karatachi no Hana, Konomichi, etc. and the opera Kurofune, includes in his autobiography episodes from the time he was an infant until the end of his study in Germany and his subsequent return to Japan. The manuscript is written on “Kōsaku Yōsen” (manuscript paper especially made to fit Yamada Kōsaku’s preferences), which contains 400 characters per page. Including the introduction, the main body and the epilogue, the document is 509 pages long.

Rhapsody of Youth has, from its first publication until 2003 (Heisei 15), including several editions with different titles decided by publishing companies, been published a total of nine times. However, Yamada’s final manuscript that was used at time of the first publication was held by the editor, Kubota Inao, until December 2009, when he kindly donated the document to Tokyo University of the Arts.

About Yamada Kōsaku and the Tokyo Academy of Music

Yamada Kōsaku studied at the Tokyo Academy of Music from 1904 (Meiji 37) until 1910 (Meiji 43). At the Tokyo Academy of Music, there was a Preparatory Course that continued into the Regular Course; there was also a Teaching Course with the aim of producing qualified teachers, but Yamada entered the Preparatory Course first. In that year, thirty-five students entered the Preparatory Course, including Yamada. Professors at the time included the sisters Kōda Nobu (piano, singing, harmony) and Kōda Kō (violin), and Tachibana Itoe (piano), amongst others. The foreign instructors included August Junker (1868–1945) and Raphael von Köber (1848–1923). In the Research Course, there were students such as Shibata Tamaki (known as Miura Tamaki after her marriage) and Okano Teiichi at this time. The Regular Course did not yet have a composition subject, so Yamada specialised in vocal studies for his graduation concert in March 1908 (Meiji 41), for which he sang Schubert’s “Der Lindenbaum” from Winterreise. While he was at the school, he also learnt to play the cello with Junker and, after graduation, he specialised in cello on the Research Course. At the October 1909 (Meiji 21) Students’ Association Concert, he played the cello part in a string quartet performance of “Serenade by Mozart”, with Oono Hisaharu, Kawakami Jun and Ootsuka Sunao playing the other parts.

While he was on the Research Course, Yamada learnt composition from the cellist Heinrich Werkmeister (1883–1936), who was invited to the academy from Germany. On Werkmeister’s recommendation, Yamada received financial support from Baron Iwasaki Koyata (1879–1945) to study abroad in Berlin at the Königlich Akademischen Hochschule für ausübende Tonkunst. Three years later, in 1912, he wrote the very first orchestral symphony by a Japanese composer, Kachidoki to Heiwa (Triumph and Peace), as his graduation work. In his final year in Berlin (1913), Yamada came into contact with the works of composers such as Richard Georg Strauss (1864–1949), Arnold Schönberg (1874–1951) and Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915), and completed his symphonic poems Madara no Hana (Flower of Mandala) and Kurai Tobira (Dark Gate).

After returning to Japan, at the same time as writing several art songs, Yamada put his efforts into increasing the prestige and performance opportunities of Japanese musicians, with the hope that musicians could gain a higher level of respect within Japanese society. As for his compositions, he used European subject matter such as “Mary of Magdala”, “Hamlet”, “Prince of Wales” and “Salome”, as well as choosing subject matter rooted in traditional Japanese entertainment and subjects containing a Japanese-like feel to them, which can be seen in his works such as Echigojishi (Echigo Lion), Mazumahakkei (Eight Sights of Mazuma), Kotobukishikisanbasou no inshou niyoru kumikyoku fuu no shukutenkyoku (Festive Music in the Style of a Suite on the Impressions of Kotobukishikisanbasou), Genji Gakuchō (Music on the Tale of Genji) and Chuugi (Devotion). An example of a fusion of these influences is the Nagauta Symphony Tsurukame of 1934 (Shōwa 9), in which he made use of the compositional techniques of Western music. He wrote an orchestral arrangement of the Nagauta song Tsurukame for orchestra, which shows his attempt to blend Western and Eastern music traditions. However, his activities were aimed at both domestic and foreign spheres; he himself formed a symphony orchestra and set up a regular concert series in Japan, yet he also gave performances of his own works in the USA, France and Russia. For the 2600th anniversary of the first Japanese emperor in 1940 (Shōwa 15), Yamada conducted Jacques François Antoine Ibert’s (1890–1962) Festive Overture, as well as the premiers of his own symphonic poem Kamikaze (Divine Wind) and his opera Kurofune (Black Ships). There were many restrictions on his activities as a musician during the Pacific War. He became the chairman of the Nihon Ongakubunka Kyoukai (Japan Association of Music Culture), which was under the jurisdiction of the propaganda-focused Information Bureau; he also formed the “Music Volunteer Corps”, with the aim of providing consolation and encouragement to the Japanese people as well as military personnel through music. This activity also included participants who were graduates of the Tokyo Academy of Music; those school students on the Research Course attended these activities and were treated as if they were attending the school, even though they missed the classes. Yamada did not teach at the academy; as an unaffiliated musician, he was critical of the government-connected Tokyo Academy of Music, yet was also admired as a role model by the students of this academy.

Following the war, Yamada’s activities during the war became the subject of much criticism aimed at him. However, from the time of his own painstaking studies as a youth, the musical scene of his childhood and his sensitivity to a wide range of music (including popular songs) would become the driving force in his later musical activities, as described in his autobiography. The troubles he had in trying to make the best of the experiences he gained as a Japanese man studying in the West are still comprehendible in modern times. This also raises several problems that are still of relevance, and even now retains its novelty.

Overview of the Document’s Writing Process

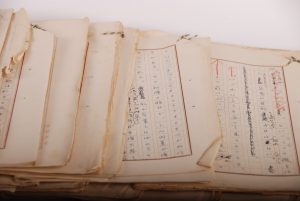

In terms of the handwriting, it can at least be said that Yamada had someone to make a complete fair copy; the handwriting of the three editors has also been identified. The handwriting of the person who made this fair copy manuscript accounts for most of the document, and to this the author made additional corrections. Yet, apart from the last few lines about the use of katakana in the “postscript”, it is all in the handwriting of the author.

By tracing the additional corrections of the author, an explanation to make the section on the old stories from his childhood more easily understood by the reader has been added to meet the publishing customs of that time. As for the section about the women he fell in love with, it seems to have been written and rewritten several times, with parts being removed for the final version. From the contents used in previous publications, one could not know about Yamada’s writing and rewriting process; however, from the digital images of this manuscript, it is hoped that this and Yamada’s past as a musician, his beliefs, dilemmas, deep sensitivity, etc. can be more vividly conveyed.

Manuscript Images

| Description | Images |

| 著作権保護期間 Copyright © |

|

Information about the Digitalisation Work

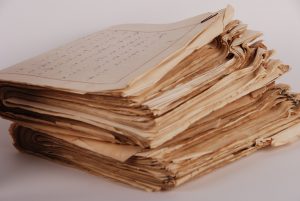

- The condition of the original document: the manuscript’s pages are, to an extent, bound by paper string. In some places, staples are used. The document has been folded in half and stored in this state. The binding was not done systematically, for instance by a decided number of pages or by the chapters, etc. Signs of deterioration can be seen in the original paper as well as the string binding, especially the fold in the page that has become the front cover, which stands out as being damaged.

- Scanned parts: as the manuscript is folded in half, fold marks and creases can often be seen in the document, measures were taken to try and smooth these out. As the condition of the deterioration and the fold marks and so on is different for each page, every page was stretched out, as needed depending on the individual fold and crease marks, and then a weight was placed on the page for several days in order to flatten out some of these creases. As for the binding etc., where possible, the individual pages were scanned and then returned and bound back to the original condition. Where the staples were used or the seriousness of the deterioration of the binding made this impossible, the pages were scanned without being removed from the original binding.

- Work undertaken by Sawahara Takamasa (Education Research Assistant, Music Department, Tokyo University of the Arts) (also author of this “Information about the Digitalisation Work” section).

- Time period over which the work was undertaken: July–October 2016.

- Machine used: KONICAMINOLTA PS5000C MKII.

- Number of pages scanned: 509.

- Scan settings: 600 dpi; the size was altered to fit the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

From the time of the donation of the document until the current stage of the images becoming public, the cooperation of especially Kubota Inao, Kubota Shizuko, Yamada Hiroko and Gotō Nobuko is very much appreciated, and we wish to thank you by writing your names here.

English Translation by Thomas Cressy

Contents developed by KAMURA,Tetsuro